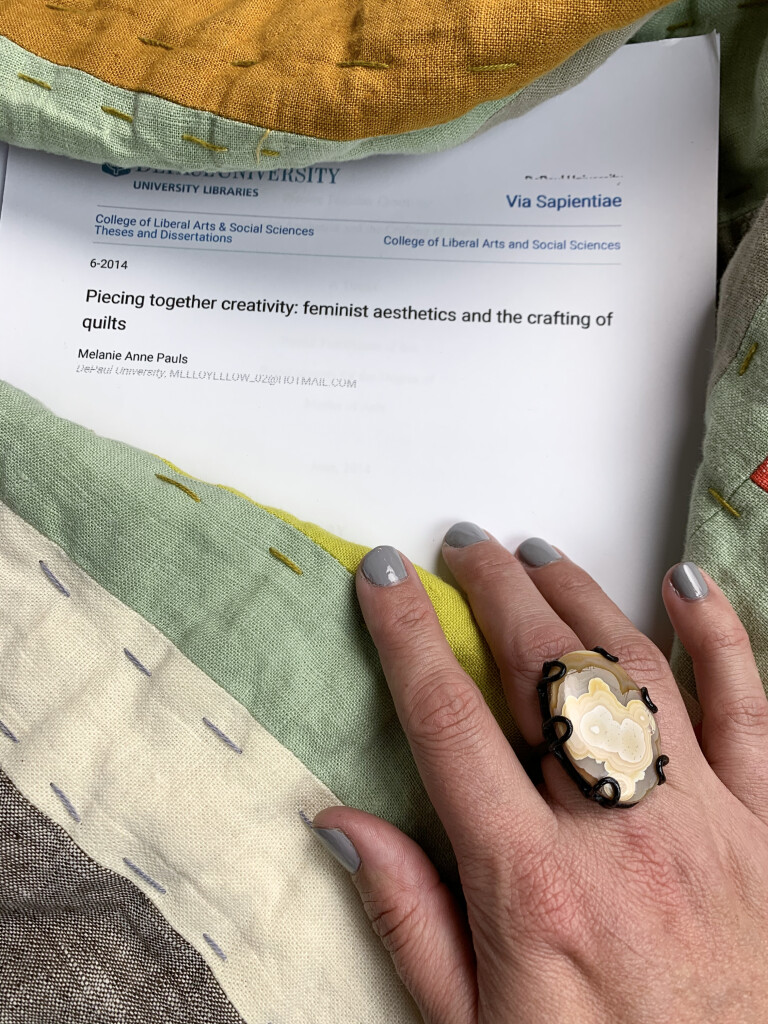

A few months ago, while searching online for an article that was mentioned in String, Felt, Thread (one of the books I read in February) I came across this Master’s thesis that had been published online in 2014 – Piecing together creativity: feminist aesthetics and the crafting of quilts by Melanie Anne Pauls. And after realizing that it spoke to many of the same themes I was interested in, I did what any total nerd would do, and proceeded to print off the full 200 page thesis so that I could read it at my leisure. (Because I really, really dislike reading on screens.)

While it wasn’t exactly a page turner (it is a thesis, after all, not a book intended for a broad audience), there were a lot of interesting points and ideas worth diving into. Rather than try to summarize all of them (since you can read the thesis online for yourself for free, and Pauls does sum up the key points well in the introduction), I want to talk about two ideas from the thesis that were particularly interesting to me: the aesthetics of modernism and the role of touch in art.

The aesthetics of modernism and its impact on what is and isn’t considered art.

One of the key points that Pauls makes throughout the thesis is the ways dominant aesthetics influence our opinion of what is and isn’t art. And while she admits that modernism is no longer the only aesthetic game in town, modernism’s outsized influence on even the current art world cannot be overstated. The emphasis on formalism, the artist as autonomous genius, and conceptualism above all else still come to play in what we think of as the “Art World.”

And it isn’t just in the Art World proper. We see the lingering effects of modernism when someone like Seth Godin dismisses certain kinds of creative practice as “merely decorative.” (Something I rant about and rebut in this post.) I also notice its lingering effects in my own world, art jewelry, where many jewelers who are trying to legitimize their work as “art” are loathe to present or photograph the work on the body. This was also a critique I had about the Met’s recent jewelry exhibition – while there was much I loved about it, for an exhibition that was subtitled “The Body Transformed” there was very little presence of the body in the way the work was displayed and discussed.

For me, what is so compelling about the role of modernist aesthetics is the way that so many groups that have been marginalized from the Art World (whether through gender, race, or even medium of expression, which of course have also been marginalized because of associations with gender and race) attempt to legitimize their work by playing into modernist aesthetics – like photographing and displaying jewelry off the body or making formalist or conceptual work using traditional craft media – rather than attempting to question the structures and definitions that led to the marginalization in the first place. In short, why so many artists and makers try to fit their work into the narrow definitions of Art through a modernist lens, rather than trying to expand the scope of what we consider art in the first place.

This is what Pauls does so well in this thesis. By interrogating these existing art world structures, she helps us see how we could expand the art world to include quilting as practiced in all it’s forms, rather than only accepting some quilts as art (and thus, only some quilters as artists) because those quilts can (intentionally or otherwise) be held up as acceptable examples of modernist aesthetics.

This is so much of what I’m interested in in my own work as well. Rather than helping artists and makers conform to a narrow model of the art world (with very narrow standards), I want to broaden the definition of art so it’s more reflective of the work more of us are making. (And thus, more relevant in people’s every day lives.)

The role (or lack there of) of touch in art.

For me, one of the most interesting, but under-explored ideas in the thesis was the role of touch in art. Pauls mentions a few times the role that touch plays in both examining and experiencing quilts, and the challenges this poses for both display and conservation. But it was her statement that the role of touch in art needs to be considered more in both practice and scholarly research that had me jumping up and down, raising my hand, and shouting “ooooh, pick me, pick me.” (At least in my head.)

Touch has been a key interest in my own art and research since my days as an undergrad. My honors thesis was entitled “Sensory Jewelry” and focused on creating jewelry that engaged all the senses. But the exhibition of that work was titled “Please Touch” as I wanted to make it abundantly clear that visitors to the gallery were encouraged to physically interact with the jewelry on display.

To this day, I often find myself thinking about the tactile qualities of not only my own jewelry, but also the other art I collect, and I love reading about sensory and bodily experiences of art and the world, with touch always being the area I am most interested in. This is most likely because I am an incredibly tactile person, someone who is happiest when my hands and fingers are engaged.

I was actually reminded of this the other day while listening to a podcast interview with Jenny Odell, the author of one of my favorite books, How to Do Nothing. In the interview, Odell talks about bringing in other areas of attention to help resist the siren song of the Internet. (More specifically, the Internet we carry around in our hands.) But what struck me was how Odell’s areas of attention seemed to focus so much on the visual and auditory. Yet, when I think of my relationship to my phone, it is as much about tactile attention as anything else. Turning my attention from my phone often means finding something else for my hands to engage with. Otherwise, my phone ends up in my hand by default, which often leads to mindless scrolling on Instagram.

It is the power of touch that, for me, makes the most compelling argument for owning and living with art. I can’t imagine a future where we’re suddenly allowed or encouraged to touch the majority of works in museums (though of course, there are exceptions – I’m reminded of this Ernesto Neto exhibition I saw ages ago), but when you own a work of art, you are free to touch and physically experience it as much as you like. This is also perhaps why I’m most drawn to collect ceramics and textiles – two areas of art where touch is a natural part of using and living with the objects.

I do spend a lot of time online trying to communicate the value of touch – it’s why I so frequently photograph myself holding things – but touch is one area where (at least for the foreseeable future) IRL will always beat out online. And as we slide into a more digital world, bringing touch into art is a way for art to not only show it’s value, but to help bring us back to ourselves.

I’m not sure what it will look like at this stage (research, writing, my actual art, or some combination of all of those) but the biggest thing I took from Paul’s thesis was a challenge to make touch a more relevant part of the conversations around and experience of art. It’s always been of interest to me, but in our increasingly digital world, it seems more important than ever.

PS. The quilt I’m lovingly touching in the above picture is by Chomp Textiles and the ring is by me. It’s not available yet, but you can join my mailing list to be the first to know when it is.

Leave a Reply