I finally found my reading groove this month, and that’s all thanks to some truly, truly incredible books. (Yes, I said truly twice, but DAMN, I read some good books this month!) What I read this month took me down two very distinct (but in some ways related) rabbit holes. Neither of these is a new research area for me, but they both really came out strongly this month.

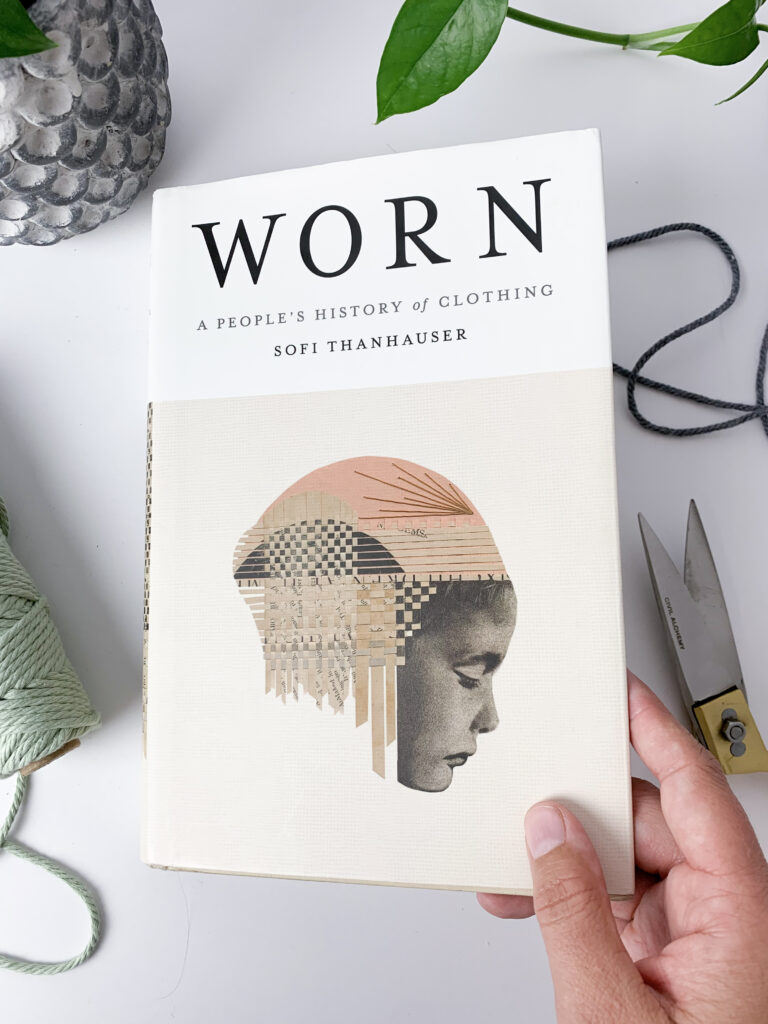

The first rabbit hole was one I would label feminist investigations of work and labor, a topic that’s its hard to ignore if you’re interested in issues related to craft and business. That rabbit hole started with Worn: A People’s History of Clothing by Sofi Thanhauser, which I picked up on my trip to Savannah in April.

Worn was such an incredible book that I gave it its own blog post, which you can read here. Worn really did touch on so many fascinating points, and if you have any interests in textiles, clothing, labor (particularly from a feminist standpoint), the effects of colonization and globalization, and the potential return of local textile manufacturing, this book is a must-read.

After making a brief and unsuccessful attempt at reading Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered (which is decidedly NOT feminist in its exploration of alternative economics), I stumbled across a book at my local bookstore that was everything I wanted Small is Beautiful to be.

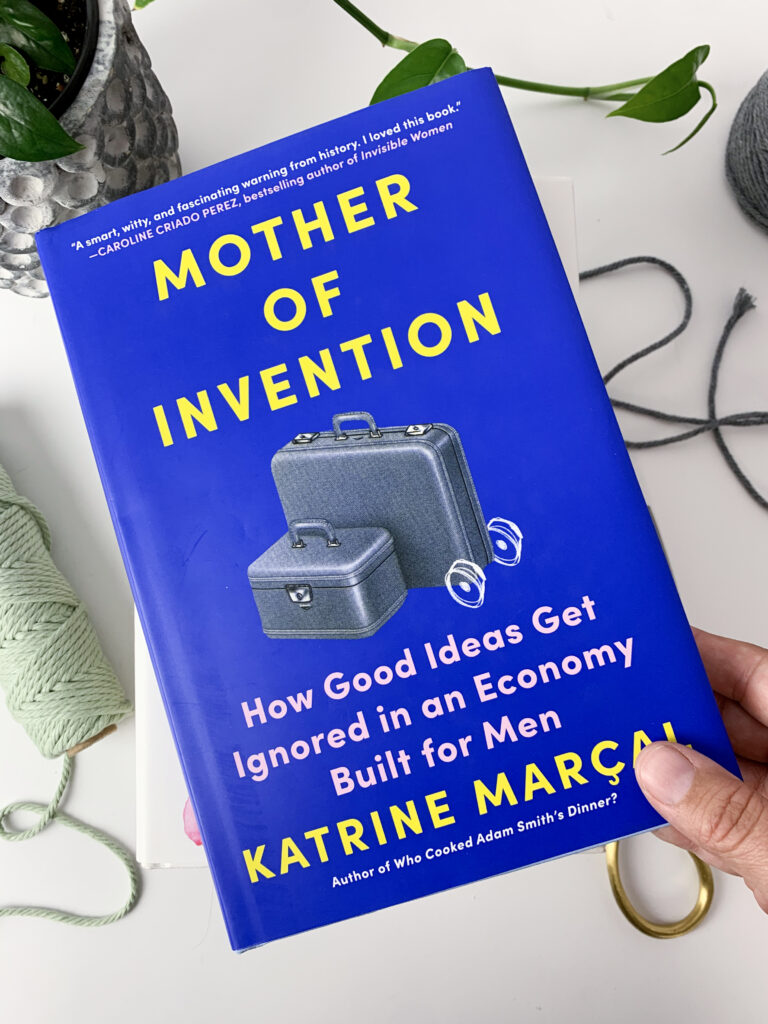

Mother of Invention: How Good Ideas Get Ignored in an Economy Built for Men by Katrine Marçal is another book that I would absolutely put on my “highly recommended” list. The book starts with explorations of products that were overlooked or underdeveloped because of feminine associations (from rolling suitcases to electric cars) before making a sweeping turn to look at how current venture capital funding models exclude women from having an impact on the world to the denigration of witches and the ways that viewing the Earth as a mother has led to our current economic crisis.

Mother of Invention does very much focus on the gender binary and the ways much of what we do is coded as male versus female, though as Marçal herself points out, the need to see things in strict gender terms is an unfortunate byproduct of living in a patriarchal societal. Overall though, I loved this sweeping exploration of what we miss in our world when we focus on masculine and patriarchal traits in our products, our funding models, and our approach to the world in general.

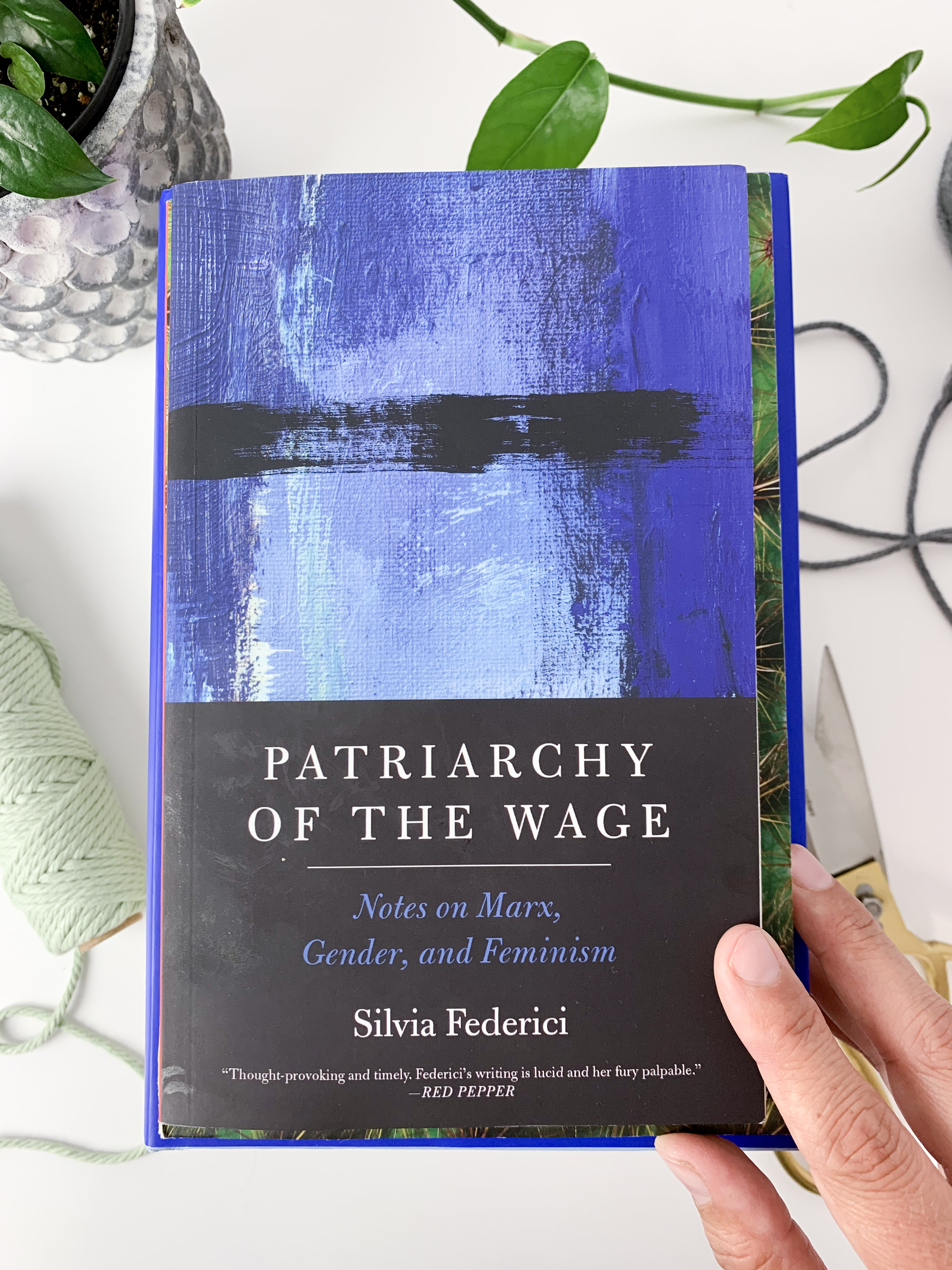

The final book I read along this theme this month was Patriarchy of the Wage: Notes on Marx, Gender, and Feminism by Silvia Federici. I loved Federici’s Beyond the Periphery of the Skin and have been wanting to dive into Patriarchy of the Wage for a while now. It ended up being the perfect complement to Mother of Invention and Worn. The book covers a number of topics related to feminism and labor, but the main crux is the way that women have been removed from Marxist theory because much of their work historically hasn’t been valued as waged labor. Federici looks at the ways that the wages for housework movement (of which she was a founding member) and other ideas can transform women’s relationship to work and the labor movement.

The second rabbit hole was my continued interest in touch and tactile engagement, something that I’ve been fascinated with since my undergrad days. But it was quite by accident that I found myself falling down this particular rabbit hole this month.

After failing to fully get into the copy of Social Chemistry: Decoding the Patterns of Human Connection by Marissa King that I picked up earlier this year, I decided to listen to the audio version. I’m pretty picky about narration when it comes to audiobooks, but this was one I could get on board with, and it felt like a good book to pass the time while driving or walking. My overall review of Social Chemistry is that it was ok. There are lots of fascinating tidbits in the book, but it really felt like it lacked an overarching theme or point to hold it together.

But one of those little tidbits was a discussion on the role of touch in social interaction. I’m not quite sure how King landed on that subject, but of course at the mention of touch, my ears perked up. And they perked up even more when King states that “There is no art dedicated to touch.” I have many thoughts on this, so many that I’ve got a full-on post in the works, but ultimately I disagree with this statement.

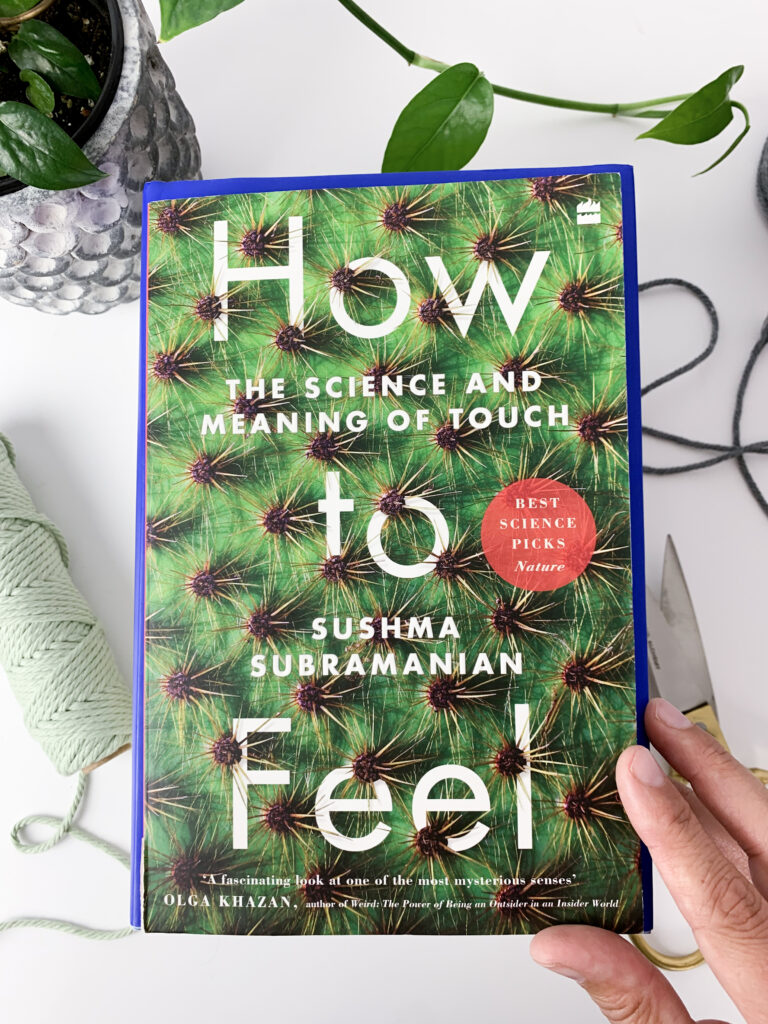

Still, King’s mention of touch had me searching a certain online bookseller for one of the books she referenced, which led me to How to Feel: The Science and Meaning of Touch by Sushma Subramanian. This book is more recent than the book King references, but it was the cover that drew me in. Or more specifically, it was the cover to the Indian edition, which is what I ended up ordering because the hardcover US edition looked terrible by comparison.

Overall, I really enjoyed How to Feel, even if, like King, Subramanian states that touch has no art of its own. (Seriously?!? Where do they keep getting this?) The book definitely has more of a bent towards science and technology than I’m personally interested in (I’m more fascinated by touch in art and handmade objects) but it’s an incredibly readable book and I think it’s a good addition to the literature on touch.

How to Feel also led me to pull The Deepest Sense: A Cultural History of Touch by Constance Classen off my shelf. I didn’t read this book in its entirety, so it didn’t make it into my stack for the month, but it’s worth mentioning here for two reasons. The first is that, while I started this book before, I never made it past the first chapter, which is why I didn’t know that later in the book, there’s an entire chapter devoted to the role of touch in museums. It was How to Feel that tipped me off to that fact, and that was the chapter that I ended up reading. But that chapter also led me to my final book of the month, Art, museums and touch by Fiona Candlin.

Despite the lack of an Oxford comma and capitalization in the title (which I’m chalking up to it being a British, academic book) I loved Art, museums and touch. The book itself was published in 2010, so it’s surprising that I’ve never come across it before. (Again, will go with it being a British, academic book on that one.) This is the most in-depth book on art and touch that I’ve ever read, and it really brought to light many ideas that have been swirling around in my head, from the role to touch in museums to the shortcomings of exhibitions that feature touch to the ways that touch is and isn’t related to gender to the ways touch does and doesn’t provide access for people with disabilities or those who are disenfranchised.

I just finished Art, museums and touch yesterday, so I’m still processing all the goodness from the book, but there are a few key points that Candlin makes that are worth noting here. The first is that she disputes the notion that art is primarily a visual medium, instead charting the ways that art historians moved art to the ocularcentric position it enjoys today. The second is the notion that sight and touch are necessarily opposites, or that touch functions as a replacement for sight. The idea that touch and sight are not opposites is something that comes up in one of my favorite books on sensory experience, The Eyes of the Skin by Juhani Pallasmaa, but it’s nice to see it addressed so clearly in Candlin’s book. And her assertion that touch in art isn’t merely a replacement for vision is something I feel strongly about too. It’s frustrating to see touch in art almost exclusively talked about in terms of people with impaired vision or blindness. While access to art for people with limited sight is a good thing, it shows a real narrowness in our appreciation of touch in art, or as Candlin puts it “as if sighted people do not touch.”

The final point that Candlin makes that I want to bring up here is the idea that touch is actually underutilized in our society, which is a premise taken by several museum exhibitions devoted to touch. Candlin points out that this is a dubious scientific assertion at best and shares how approaching touch in this way denies all the ways we can and do experience touch in modern society. I’ll admit that I’ve taken this position myself, that we do not appreciate touch in our modern world, and Candlin’s arguments made me question that approach.

While Candlin doesn’t state this directly, I think a lot of the literature on touch and the lack of touch in modern society comes from the fact that to justify touch as a topic worthy of study or publication, we need to present touch (or the lack thereof) as a problem to be solved. As a culture, we are so focused on ways that we can solve problems or justify things with science that we can’t just write about touch as what it can also be – a source of aesthetic pleasure.

Candlin’s argument has me thinking more about how I want to approach art and touch in my own research and writing and the ways I want to focus less on the problem of lack of touch in art and more on the joys that come from experiencing art through touch.

Leave a Reply