Well, it’s safe to say my reading slump is over since I finished six books in May! It’s also pretty safe to say that I find it easier to write when I’m reading regularly since I also completed over 30k words on my next book this month! (If you’re curious what that book is about, make sure you join my mailing list. I’m hoping to announce it in early July.)

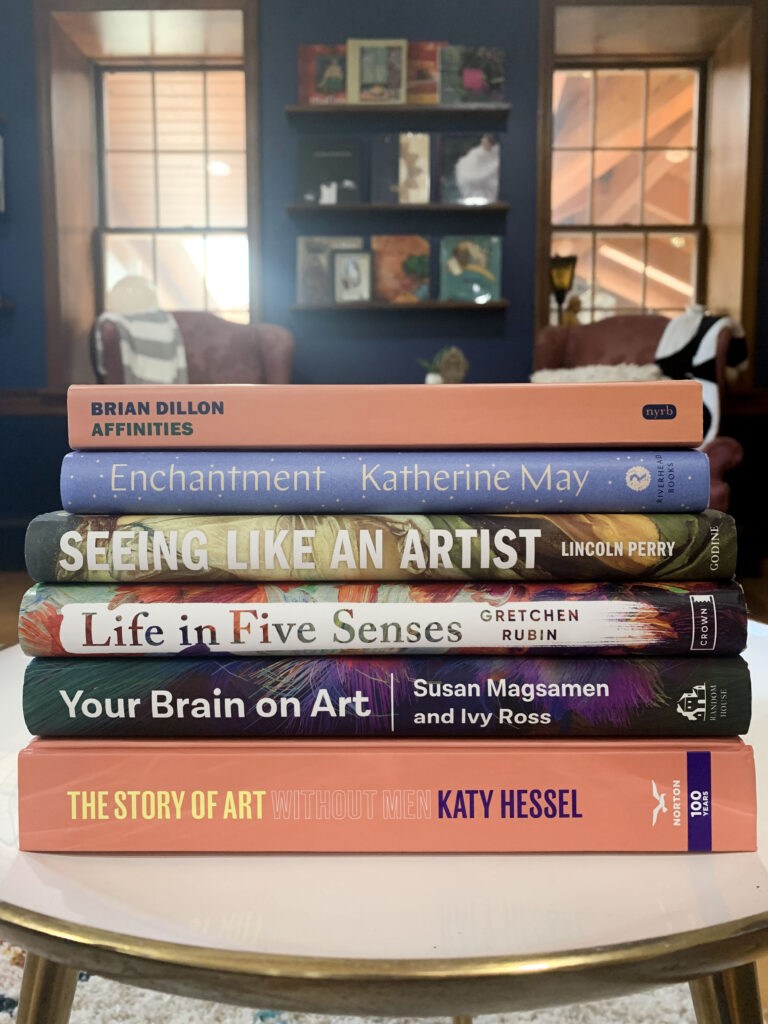

It’s also pretty clear that my reading had a theme this month, as I hunkered deep into books about art and aesthetics. (Which is why it was only fitting that I photographed these books in my new art library.)

The first book I read was probably the furthest afield from those topics. I’ll admit that I’ve had Katherine May’s previous book, Wintering, on my TBR pile since it came out, but that didn’t stop me from buying her new book, Enchantment, when I saw it at the store. And for whatever reason, I decided this was the one I was going to tackle first. What I find interesting about this book is that it feels like it was positioned as a self-help book, when in reality, it’s more like meandering thoughts on nature, life, and the experience of enchantment. If we’re being honest, that is much more my genre than straight-up self-help, so I was happy about that. But I can’t say I loved this book. I like it, and certain passages really struck me, but my overall impression was that’s its a solid book, but not one I’m going to run around shouting about.

The same could also be said for Lincoln Perry’s Seeing Like an Artist. I picked this book up back in December when I was in Savannah, but it took me getting out of my reading slump to finally tackle it. I’m all for any book that talks about the experience of viewing art, and like May’s book, there were passages I liked, even if I didn’t love the overall book. Part of the challenge with this book is that Perry is an old, white dude, and sometimes he writes like a curmudgeonly old, white dude. Like when he talks about giving his student shit for not getting to Europe to see old masters. Dude, Europe is way more expensive to visit than when you were young, and it’s not the only place to see art. That is probably my biggest gripe about the book, that it really focuses on viewing art from a Euro-patriarchal lens. But at the same time, there were parts – descriptions and discussions – that I still enjoyed.

One book that I’ve been curious yet skeptical about since I first heard about it was Gretchen Rubin’s Life in Five Senses. My initial reaction to this book is akin to hearing someone talk about a great new band they “discovered” that I’ve actually been in love with for twenty years. And in that case, I mean that literally. It’s been exactly twenty years since I wrote my undergraduate thesis on sensory jewelry. Still, I’m happy anytime discussions of the sensory experience enter the mainstream, and so I approached this book with cautious optimism. And I’ll be honest, I was pleasantly surprised. It probably helped that as part of her five senses project, Rubin committed to visiting the same place every day for a year (or, every day she was home) and that place just happens to be (despite it’s flaws) one of my favorite places in the world, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. I was also impressed at how much reading the book had me paying attention to my own sensory experiences of the world, which is saying something, as I already do that a fair bit. I wouldn’t say that anything in the book was earth-shattering (but again, I’ve been interested in this topic for twenty years) but I found the book more enjoyable than I expected.

Another book that I was excited about since it came onto my radar is Katy Hessel’s The Story of Art Without Men. This was published in the UK last year and I’ve been eagerly awaiting its release in the US. When I was in undergrad, I took a course titled “Women in Art,” thinking that it would be a survey of women artists. Instead, most disappointingly, it was a class about depictions of women in art. Hessel’s book represents the class I wish I had been able to take. Admittedly, it reads a bit like a textbook, which honestly, I hope many professors start using it for foundational surveys of women artists. There were plenty of artists in the book I was already familiar with, but it also introduced me to some I want to learn more about, or helped me to see some artists with fresh eyes. I did find the book a little painting and sculpture-heavy, despite Hessel’s best attempts to add in work in what is traditionally considered craft media. (Textiles is the area where she is includes the most.) Still, I think this book should be a resource for any artist who wants a good survey of women artists.

What I found interesting is that several of the artists mentioned by Hessel also featured prominently in Affinities: Notes on Art and Fascination by Brian Dillon. Quite frankly, I only picked this book up because I noticed both the cover and the title at my local bookstore (which was just named Bookstore of the Year by Publisher’s Weekly) without really looking into what it was about. I expected it to be more of a discussion on what it is about art that fascinates us. Instead, it features a series of essays on various pieces of art (most of which were photographs, despite the use of a painting on the cover) that Dillon finds fascinating, as well as essays on the nature of affinity. But even though it wasn’t what I expected, I did find the essays enjoyable and it made for an interesting companion read to Hessel’s book.

The final book I read this month was one that people keep recommending to me, even though it’s been on my radar for months. I want to give Your Brain on Art by Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross a glowing recommendation, but sadly, I only feel lukewarm about it. First off, I’m happy to see any book that helps show why the arts are essential to our world. Please, please, please, publishers, let’s have more books on this topic. And I learned A LOT about how the arts impact our brains and bodies. But I also found the book a little bit tedious (I ended up purchasing the audiobook and listening to it at 1.2x speed) and repetitive, while at the same time, glossing over the surface in a lot of areas. My brother-in-law and I have a joke about books like this, noting how we “read a book about a book about that” and that’s what this felt like. Lots of mentions of various scientific studies.

And I think that’s my biggest critique of the book. I’m all for science, but this felt like trying to slam us over the head with PROOF. It very much felt like, “Here, now we know the arts are valuable because science told us so.” For me, that makes one of the most poignant and ironic parts of the whole book a conversation with Māori artist and musician Jerome Kavanagh. Kavanagh recounts an inside joke that happens when people from his community see the results of scientific studies on things that they’ve transmitted as ancient wisdom through art and story. The authors share this statement from Kavanaugh: “Wow, we already knew that. We were taught that stuff when we were little kids. And only now, they’re making a scientific discovery.” I’ll admit that’s how I felt about this book. These are things I’ve known since I was a kid, taking drawing classes and making art in my parent’s living room. On one hand, I’m glad science has caught up, and we finally have some proof for why the arts matter. On the other hand, I hate that we needed the proof in the first place. Because it shouldn’t take a scientific study for people to see what artists have known for so long – that art makes the world a better place.

Leave a Reply