I’m going to do my best to keep this from becoming a rant, but no promises.

crafting an MBA – business thinking for designers & makers

the cost of the cozy/cuff

clarity and certainty

Today was one of those rare days where suddenly I can clearly see the direction I want to be headed in. I feel like I’ve been spinning lately, but can now see a path out of the chaos. I’m not quite ready to expand on the details, but I wanted to document how I was feeling. Because right now I am feeling sure and certain. And excited. And tired. (Ok, that last one is only because I’m coming off a long day of teaching, so its time to say goodnight.)

moomah

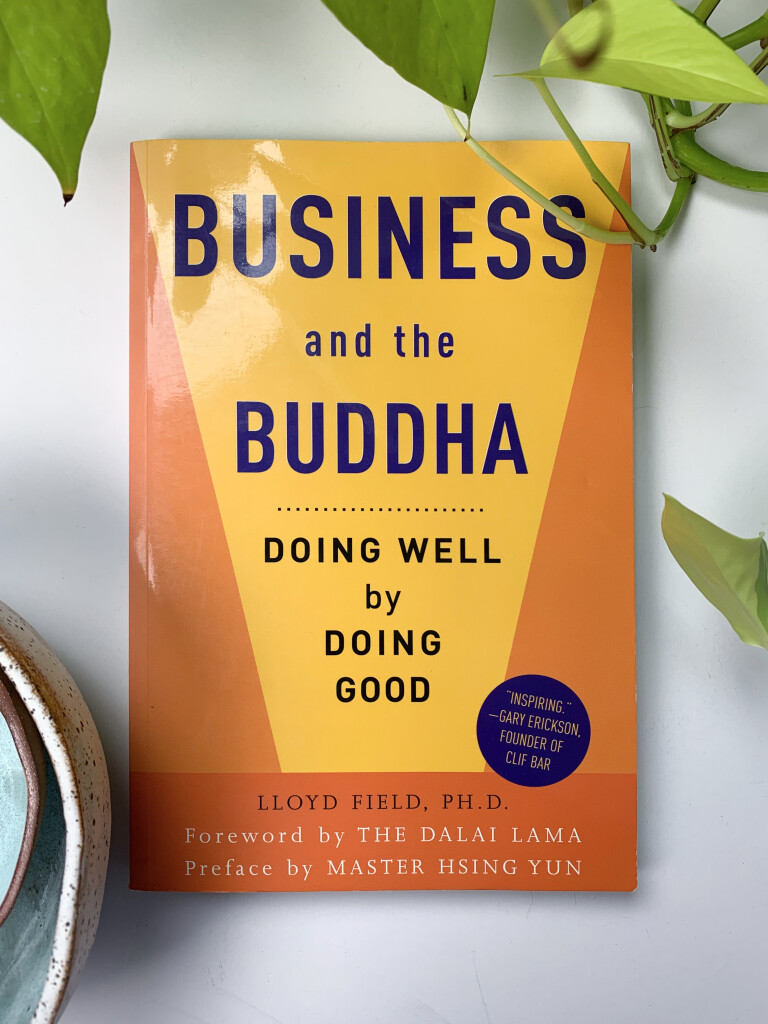

what I’m reading: business and the buddha

Since I’m thinking more about the kind of business I want to have, and the importance of creating value (and not just making money), I pulled Business and the Buddha from my stack of “to be read” books.

I didn’t really find most of the ideas in the book earth shattering (though perhaps they would be if I was the CEO of GM or some other company like that). Instead, they reinforced what I’ve already been thinking about. Author Lloyd Field stresses that the primary goal of any business should be to “Cause No Harm,” whether it be to the environment, employees, or customers. Field then goes through Buddhist principals to help clarify how a business can “Cause No Harm” and “Create a Better Society.”

One of the most important ideas I took from the book was my need to create a value statement. Its clear to me that in my business, my goal isn’t just to create profit, but I really need to clarify my values and communicate those to my customers as well.

create (value) every day

As some of you may have noticed, I did not attend this year’s SNAG conference. But I did have one of my friends pick up some information from the Professional Development Seminar for me. I was curious to know how the information was similar or different from what I had presented the previous year.

gift fair wrap-up

I took yesterday off to decompress and relax after a long gift fair week (not to mention a stressful few weeks getting ready for the show).

I took yesterday off to decompress and relax after a long gift fair week (not to mention a stressful few weeks getting ready for the show).

what I’m reading: buying in

I just finished Rob Walker’s book Buying In: The Secret Dialogue Between What We Buy and Who We Are. Walker writes the column Consumed for the New York Times Magazine, as well as a the blog murketing. The beginning of the book details the transition for tradition marketing to murketing (murky marketing), a term coined by Walker to define marketing attempts that exist outside the traditional realm. If you’ve been paying attention at all since the turn of the century, this isn’t really anything new. As TIVO and the internet divert peoples’ attention away from traditional mass-market advertising, companies have had to develop new strategies to market their products. Not really new information.

It wasn’t until chapter eleven, then, that I sat up and payed attention. Walker profiles Aaron Bodaroff, who set out to answer the question, “How do I turn my lifestyle into a business?” This struck me for two reasons. One I’ve been asking myself a similar question lately. Namely, how do I take the things I really want to do, and make them into a business? But more so, it is actually the opposite question around which I’ve attempted to build my business, “How do I turn my business into my lifestyle?” Or more so, “How do I turn myself into my own brand?”

In building my brand, I’ve (hopefully) communicated a brand with a strong aesthetic based around graphic, modern, organic designs and a black, white, and gray color palette. By virtue of the fact that jewelry is one of the few art forms you can advertise by wearing, it seems as though my aesthetic (and therefore my brand) has infiltrated its way into my daily appearance. I was becoming my own brand. Which, according to Walker, my generation sees as a “legitimate form of creative expression.”

But defining myself in such a narrow way (through the lens of my business/brand), may be what has contributed to my recent boredom and my desire to more fully explore other interests. My desire to be more than just a business contributing to an endless stream of consumption has led me to consider other problems such as sustainability, environmentalism, and business ethics. Fortunately for me, Walker addresses these as well. And if chapter eleven made me sit up and take note, chapter twelve resonated with me in terms of a usable business/marketing model.

Or perhaps I should say, an unusable marketing model. According to recent polls, a majority of consumers are increasingly interested in making ethical purchasing choices. (I’m paraphrasing here.) Yet, according to Walker, this majority does not translate to the marketplace. While socially-conscious purchases are on the rise, they in no way reflect the majority of respondents who claim interest in ethical purchasing. Ethically-minded purchasing (whether green, fair-trade, organic, etc.) remains a niche-market. Case in point, American Apparel. Even though the company’s philosophy is based on ethical business practices, they chose a broader, mass market ad campaign based on sex-appeal.

As I read this, I kept thinking this could be a problem for the indie-craft field, whose main marketing ploy is an ethical choice – support independent artists and handmade objects rather than mass-produced items and big business. Gabriel’s post last week on Conceptual Metalsmithing, titled “The Green, The Organic, and The Handmade,” examines this further. Gabriel draws parallels between green and organic impulses and the desire to buy handmade, which I agree with. Gabriel argues that we as craftspeople should draw on the same ethical shopping desires motivating people to buy green or buy organic. But if you expand on Walker’s argument, by positioning craft in a niche market of ethical consumerism, we may never have relevance to a larger market of consumers.

In the next chapter, Walker actually goes on to talk about the DIY movement, including Etsy and the Austin Craft Mafia. Walker describes the DIY movement as a political movement grounded in consumption and marketing. One of the comments that struck me most details the awkward growth that the indie-craft movement is starting to face. We can all only make so much by hand, and at some point we either have to accept that we have hit our maximum level, or consider outsourcing, hiring help, etc. This can lead crafters to, as Walker describes, “the Courtney Love syndrome: too weird for the main stream, but successful enough to be seen as a sellout by ‘the underground that once loved you.'” Which is how I’m starting to feel about my business. Not that I’m that successful, but rather I’m learning that to truly have a sustainable (in the financial sense) business, I might have to let go of some of the handmade idealism that helped me get started in the first place.

Verdict: While the beginning seems a little obvious, there aren’t many books that actually discuss the DIY craft movement. But even if it didn’t, Buying In would still be a worthwhile read for indie craft artists who are trying to understand how they fit into the contemporary marketplace.

spiritual capitalism

I just read this article from Ode Magazine called “The gospel according to Adam Smith.” The article focuses on spiritual capitalism – the idea that doing good can be synonymous with making money.

I was immediately reminded of a company I came across the other day – Kind Bike. I loved Kind’s mission statement so much that I wish I could steal it for my own:

“We believe the triple bottom line – people, planet and profits – should be at the core of every company’s value system.

We believe that any product should have value beyond mere possession.

We believe that simple and easy should translate into every aspect in which a company is involved.”

The article also mentions a book called Business and the Buddha: Doing Well by Doing Good. This is definitely going on my must read list.

(Thanks to Christina from Taboo Studio for introducing me to Ode!)