by Megan Auman

Note: The following text is from my MFA thesis, originally exhibited and published in 2006 at Kent State University.

INTRODUCTION

As the title suggests, my thesis re-examines the way we view domesticity and the contemporary home by utilizing a series of dualities, such as hard/soft, structure/surface, production/consumption, and comfort/display. Most of these pairings also function as stereotypical qualities of the masculine and feminine. These opposing concepts exist in the contemporary home, and are exaggerated in my thesis installation.

My thesis occurs during a time of renewed interest in domesticity and the home, both on a visual and theoretical level. An abundance of home-themed books, magazines, stores, catalogs, and television shows and networks reflect our ever-growing interest with the way our homes look and feel. According to Virginia Postrel in her book The Substance of Style we are experiencing a renewed interest in aesthetics.

This interest parallels a return to floral patterned decoration in the home – a central theme in my thesis that I will return to later. This rising interest in the domestic sphere encompasses a return to the home as haven, as we once again call on the home to function as a safeguard of traditionalism and values in the face of cultural upheaval.

In addition to examining the role of domesticity in the contemporary home, my thesis draws heavily on research about the development of domesticity during the Victorian era. The contemporary home owes much to the ideas of domesticity and decoration developed during the Victorian era. The formal living room can be traced directly to the Victorian parlor or sitting room. Contemporary notions of comfort and display have their roots in Victorian sensibilities. Conversely, our concepts of acceptable decoration and displays of gender have developed from the Modernists’ reactions against Victorianism.

HARD AND SOFT: METHODS AND MATERIALS

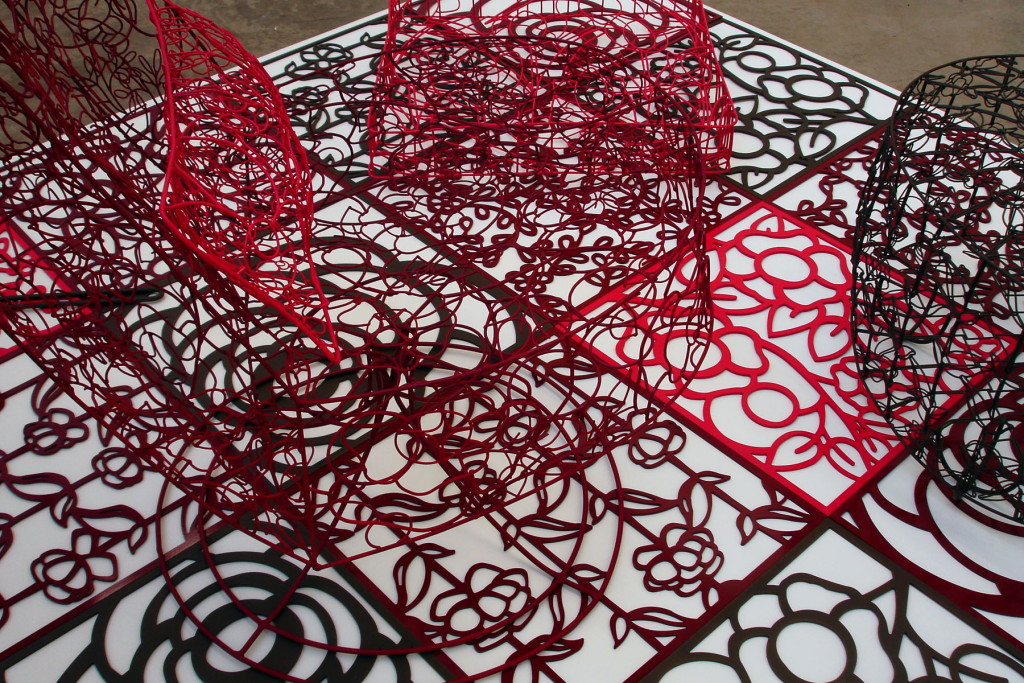

The thesis itself is a singular sculpture displayed on a riser in the center of the gallery. The sculpture, simply titled living room, consists of a chair, ottoman, pillows, lamp, and floor panels, all fabricated in steel and powder-coated. The chair, ottoman, lamp, and pillows are each made by welding steel wire of various diameters. The floor panels are made from laser-cut steel plate.

My thesis is a continuation of my interest in rendering familiar objects in unexpected materials. This allows for a re-reading of the objects presented. By rendering furniture in a hard, durable material such as steel, I interrogate notions of comfort. The pieces are composed of floral patterns rendered in wire. I weld each piece with an oxy/acetylene torch. Despite the fact that welding conjures images of large-scale, masculine, steel sculpture, I translate the process into a feminine, solitary, delicate activity. The intricate details of my floral designs, and the intimacy of the torch welding process, function for me in a similar way to the process of embroidery, which is often linked to domesticity and femininity.

My process for constructing the furniture pieces mimics the way one might work with fabric to upholster furniture. Each wire floral design is created as a flat panel, which is engineered to fit a certain area of the piece of furniture. Each panel is then formed to the desired shape, and the panels are joined together with a heavier gauge wire, which stands in for the piping often found on the edges of upholstered pieces.

SURFACE AND STRUCTURE: THE HISTORY AND USE OF FLORAL PATTERNS IN THE HOME

One of the most visually prominent features of my thesis is the use of a variety of floral patterns layered throughout the piece. One rarely encounters a contemporary home with the intensity of pattern and decoration that occurs in my thesis, yet this riotous use of pattern was commonplace in the Victorian era of the mid- to late 19th century. The floral patterns of the Victorian era played a critical role in the creation of comfort and domesticity. The condemnation of the ‘cluttered, mismatched, excessive’ Victorian interior, and the subsequent reorganization and removal of floral decoration in the home parallel the devaluation of the home and women’s role within it.

The proliferation of floral patterns in the Victorian domestic interior was the result of both technological and sociological developments. The industrial revolution allowed the rapid production of large quantities of textiles, at the same time that the rise of the middle class, with its newfound income, led to a greater demand for them.

The rise of new technologies created printing and dying techniques in textiles that were well suited to the representation of larger, more naturalistic floral imagery, such as those that occurred on glazed cotton chintzes, often used for upholstery. The push for novelty in printed textiles made design a secondary consideration.

These textile patterns were not based on any traditional pattern organizational structure, rather their goal was to recreate the disorganization of nature as truthfully as possibly.

The industrial revolution also ensured that the home remained important as a safeguard of traditional values in the face of cultural upheaval. The vast technological changes in the public sphere were met with traditionalism and naturalism in the domestic sphere. Floral patterned textiles were a key component of the trend towards both naturalism and traditionalism, which was seen as a counterpoint to the newly mechanized world.

In addition to printed textiles, floral imagery also appeared in embroidery throughout the home. With this activity, the housewife added additional visual indications of comfort, and enforced values of beauty, morality, and femininity, all of which are traditionally linked to both flowers and embroidery. Creating embroidered objects for the home also allowed the housewife to participate in aesthetic decision making within the home in a capacity beyond that of consumer.

As women exercised a greater and greater role in the decoration of their homes, their aesthetic expressions – particularly their use of excessive floral patterns – came under attack. The second half of the 19th century saw several reform movements, which sought to remove the decoration of the home from the amateur and irrational woman and give it instead to trained designers, who were typically male. The earliest reform movements, such as the Arts and Crafts Movement, perpetuated the use of floral patterns in the home. The change occurred in the style of patterns themselves, which featured logical organization systems and simplified and stylized flowers. As these reform movements became commonplace, women’s ability to decorate their homes was called into question, and the value of domesticity and feminine household skills began to decline.

The 20th century witnessed the removal of floral patterns from the domestic interior, as part of a broader rejection of ornament. Writing in 1925, Le Corbusier criticized the falsehood of ornament and floral decoration for its emphasis on surface over structure.

Ornamentation, particularly of the floral and naturalistic varieties, was criticized for being deceptive, seductive, fickle, and false – in short, feminine.

While the modernist design cannon dominated for most of the 20th century, the late 20th century saw the beginnings of a return to floral decoration. Not surprisingly, this return to floral decoration coincides with the renewed interest in domesticity and the home. By adding my work to the vocabulary of contemporary floral design, I rebuke the modernist notion that surface is secondary to structure by tying the two together.

HANDMADE VERSUS MANUFACTURED: THE ROLE OF TECHNOLOGY IN FLORAL PATTERN DESIGN

Domestic floral patterns have developed both because of and as a reaction to the development of new technologies. As we have seen, technological advancements during the industrial revolution made floral patterned textiles more desirable and widely available. Today, the renewed use of floral patterned textiles is again influenced by new technologies. Laser cut fabric and computer generated embroidery mark a return to disorganized floral patterns. Some of the most important technological developments have occurred in the area of printed textiles, with the advent of digital printing technologies.

Traditionally, the printing media determines the size of textile pattern repeats. Block-printed textiles necessitated small repeat sizes. Roller and screen-printed allowed for slightly larger repeats, but textile patterns still required a repeat to create long lengths of yardage.

With digital textile production, the need for repeat patterns is eliminated, as the printer is connected to a computer. This means that large amounts of yardage can be created without ever needing to have a repeat in the pattern. Designers are also using this technology to create patterns based on repeats where subtle changes occur throughout the entire fabric.

Ironically, these new technologies allow textile production to embrace many of the same traits that are indicative of a hand-made object.

The potential for non-repeat patterns created by digital textile production influenced the designs I created for my thesis. I created each of the floral patterns on the computer by basing the designs on repeat patterns but then creating variation. For the chair, I created a basic pattern with a vertical repeat, but shifted the scale of the flowers, so that they get larger as the pattern approaches the bottom of the chair. In the ottoman, a leaf and stem pattern is repeated, but the flowers are randomly placed throughout the entire piece. On the top of the ottoman, I employed an engineered pattern, meaning the pattern is designed to fit the shape and size of the piece. I employed these three techniques – scale shift, randomization, and engineered patterns – in various ways throughout each of the objects in my thesis.

Technology also plays a role in my thesis through the use of laser-cut floor panels. These panels mimic the FLOR™ carpet squares that are commercially available. FLOR™ is a series of modular carpet tiles, approximately 20” in each direction, available in both plain and patterned designs. To create the steel panels, my designs were redrawn in the computer and then laser cut, a process by which a computer-controlled laser cuts designs from plate metal. By using these manufactured panels, I set up an obvious tension between the handmade furnishings and the machined floor tiles.

The final area where technology comes to play is in both my color choices and method of applying the color. The red and pink were chosen for their references to colors first made widely available through chemical dyes created during the industrial revolution. The colors were also chosen for their overt reference to femininity. The color was achieved through the process of powder coating – an industrial process that creates a hard, durable coating onto metal. This process is used on the majority of commercially available metal products, and serves as yet another representation of the influence of technology in domestic design.

PRODUCTION VERSUS CONSUMPTION: DOMESTIC FANTASY AND THE MARTHA STEWART IDEAL

One of the criticisms of the Victorian home – as well as the contemporary home – is its reliance on consumerism. Consumerism is most often seen as a negative trait, linked to passiveness, domesticity, and femininity.

Yet in the Victorian home, consumer goods and handmade objects were mixed freely to evoke the desired effects. And while the Victorian housewife spent much time and energy shopping for the newly available consumer goods, this was hardly a passive activity. Rather, the selection and arrangement of objects in and for the home could be considered an important form of aesthetic expression.

In our contemporary culture, there is no better example of the mix of both domestic consumption and production than Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia, Inc. Martha Stewart, as the public face of MSLO, offers a model for the hand made object in the home, while simultaneously encouraging consumerism through her myriad of mass-produced, commercially available products. Stewart presents a “fantasy of an upper class life-style” that “validates women’s interest in domesticity.”

Stewart comes under attack for both her expressions of consumerism and her creation of impossible standards for women to live up to. She inhabits a fantasy world where hand labor can create the ideal room, the ideal home, the ideal life. Yet, critics of Stewart ignore the fact that fantasy can be an important aspect of everyday life. For fans of Stewart, making the projects she presents allows them to simultaneously be grounded in the reality of their own bodies and escape into fantasy.

Obsessive, hand making is clearly an important aspect of my thesis, yet the work openly references objects that are typically purchased for the home. The thesis has been an opportunity to take control of my own domestic fantasy, and explore an alternative to the ‘passiveness’ of consumption. Just as Stewart legitimizes domesticity for many women, my thesis attempts to legitimize the marginalized activity of domestic aesthetic production.

COMFORT VERSUS DISPLAY: “THE NEW LOOK OF COMFORT”

One of the most obvious readings of my work is the tension between comfort and display in the home. This trend is not new, but rather a continuation of the masculine and feminine roles that the home developed during the Victorian era.

One of the main jobs of the Victorian housewife was to ensure that the home, and everything in it, embodied, through visual and symbolic effects, comfort. According to Penny Sparke, in her book, As Long As Its Pink, “the idea of physical comfort could be expressed by cushioning, soft textures and surfaces, by gentle curved forms and patterns rather than harsh, geometric ones, and by visual references to the natural world rather than to the man-made world of technology.”

To ensure this effect, these elements were layered throughout the home in staggering numbers. This emphasis on comfort helped to enforce the role of the home as haven from a rapidly changing world. By emphasizing comfortable, natural forms in the home, the housewife ensured that she was fulfilling her role as sustainer of values through aesthetic decision-making. The need for comfort often occurred alongside the housewife’s other role – to create displays in the home that were at the height of contemporary fashion. This included the use of newly available fabrics and furnishings, as well as display of the housewife’s finest needlework.

Just as in the Victorian era, the battle between comfort and display still exists in the contemporary home, as do the gender roles that developed during that time. The privileging of comfort over aesthetic seems to be considered a masculine desire, perhaps best seen in the La-Z-Boy recliner we assume every man to want and every woman to despise. The desire for display first – seen in the heaps of unusable pillows on the couch or bed—is seen as a frivolous, feminine trait.

However, there seems to be a new understanding of the roles both comfort and display play in the contemporary home. La-Z-Boy’s recent ad campaign, “the new look of comfort,”attempts to re-establish the company as one who caters to the need for both comfort and aesthetics. And despite their supposed uselessness, those stacks of pillows still imply, at least visually, the Victorian characteristics of comfort.

At first glance, my thesis installation seems to privilege display over comfort, potentially creating a critique of this highly feminized space. However, despite the choice of a hard material, all the visual cues of comfort remain. The seat and back of the chair curve to fit the body. The pillows appear plump and soft. My goal is to remind the viewer that our understanding of comfort initially comes from visual cues. So while my space appears to privilege display, it has all the indications of a comfortable, inviting room.

FEMININE/MASCULINE: THE ROLE OF THE BODY IN THE HOME

In her article, “The Knowledge of the Body and the Presence of History,” Deborah Fausch claims that a feminist architecture is one that “fosters an awareness of and posits a value to the experience of the concrete, the sensual, the bodily – if it uses the body as a necessary instrument in absorbing the content of the experience.”

It could then be argued that despite its celebration of the feminine through floral decoration and obsessive making, the display of my thesis does not allow a feminist reading of the work. Kept at arms length, the viewer is forced to visualize herself in the space. The piece sets up a conflict between a masculine (logical) and feminine (corporeal) way of understanding the objects.

While our fantasy of furniture is best mediated through the visual, our everyday interactions with furniture are grounded in the body. By presenting the work purely as display, I evoke a sense of longing. The piece becomes the ultimate expression of female desire – a place best understood through the body that can only be experienced visually.

CONCLUSION

My thesis allowed me to re-examine the way I view domesticity in the contemporary home. By interrogating the cultural forces that affect the domestic sphere, I came to better understand my own preferences for the decoration of homes. My thesis expanded my interest in floral patterns, both for their aesthetic value and their ability to represent domesticity. While the renewed interest in floral patterns parallels a broader interest in the home, my interrogation of floral patterned textiles corresponds with my own growing interest in the overlapping of femininity and domesticity in contemporary society.

NOTES

1 Virginia Postrel, The Substance of Style: how the rise of aesthetic value is remaking commerce, culture, and consciousness (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2003) p. 5

2 Penny Sparke, As Long As It’s Pink: The Sexual Politics of Taste (London: Pandora, 1995)

3 Linda Parry, The Victoria and Albert Museum’s Textile Collection: British Textiles from 1850 to 1900 (New York: Canopy Books, 1993) p. 9

4 ibid., pp. 9-10

5 Sparke, pp. 36-7

6 ibid., p. 37

7 ibid., pp. 50-69

8 Le Corbusier, “The Decorative Art of Today” in Isabelle Frank, ed, The Theory of Decorative Art: An Anthology of European & American Writings 1750-1940 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000) pp. 213-218

9 Jennifer Harris, ed, Textiles, 5,000 Years: An International History and Illustrated Survey (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1993) p. 225

10 Cathy Treadaway, “Digital Imagination: The Impact of Digital Imaging on Printed Textiles” Textile: The Journal of Cloth and Culture (November 2004) pp. 258-273

11 Henry A. Giroux, Breaking in to the Movies: Film and the Culture of Politics (Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers, 2002) pp. 260-1

12 Sparke, p. 30

13 Ann Mason and Marian Meyers, “Living With Martha Stewart Media: Chosen Domesticity in the Experience of Fans.” Journal of Communication (December 2001) pp. 810,819

14 Sparke, p. 27

15 As seen in La-Z-Boy television and print advertising.

1614 Deborah Fausch, “The Knowledge of the Body and the Presence of History: Toward a Feminist Architecture.” In Amelia Jones, ed, The Feminism and Visual Culture Reader (New York: Routledge, 2003) p. 427

Bibliography

Coleman, Brian D. Vintage Victorian Textiles. Schiffer Publishing Ltd., Atglen, PA. 2002

Gere, Charlotte. Nineteenth-Century Decoration: The Art of the Interior. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York. 1989.

Grier, Katherine C. Culture & Comfort: People, Parlors, and Upholstery 1850-1930. University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, MA. 1988.

Halsey, Elizabeth T. Ladies Home Journal Book of Interior Decoration. Curtis Publishing Co., Philadelphia. 1957.

Harris, Jennifer, ed. Textiles: 5,000 Years. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York. 1993.

Hefford, Wendy. Design for Printed Textiles in England from 1750 to 1850. Abbeville Press, Inc., New York. 1992.

Ikoku, Ngozi. British Textile Design from 1940 to the Present. V&A Publications, London. 1999.

Leopold, Allison Kyle. Victorian Splendor. Stewart, Tabori & Chang, New York. 1986.

Mayhew, Edgar deN. A Documentary History of American Interiors. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York. 1980.

Mendes, Valerie. British Textiles from 1900 to 1937. Abbeville Press, Inc., New York. 1992.

Miller, Judith. The Style Sourcebook. Stewart, Tabori & Chang, New York. 1998.

Morton, Ruth. The Home – its furnishings and equipment. McGraw-Hill, Inc., New York. 1970.

Paine, Melanie. The Textile Art in Interior Design. Simon and Schuster, New York. 1990.

Parry, Linda. British Textiles from 1850 to 1900. Abbeville Press, Inc., New York. 1993.

Peabody, Henrietta C. Inside the House Beautiful. Little, Brown, and Co., Boston. 1925.

Peck, Amelia [et al]. Period rooms in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York. 1996.

Pile, John. A History of Interior Design. Calmann & King, LTD., London. 2000.

Proctor, Molly G. Victorian Canvas Work. B. T. Batsford, LTD., London. 1986.

Rutt, Anna H. Home Furnishing. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York. 1948.

Stepat-De Van, Dorothy. Introduction to home furnishings. Macmillan Publishing Co., New York. 1971.

Whiton, Sherrill and Stanley Abercrombie. Interior design and decoration. Pearson Education., Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. 2002.